This story originally appeared on louisvillewater.com on September 17, 2019. For the original story, visit https://louisvillewater.com/news/a-promising-new-product/.

Louisville Water employees have been developing a unique solution to the problem of lead leaching into water because of old plumbing.

Louisville’s drinking water does not contain lead when it leaves the treatment plant. Lead becomes a potential risk only when the water travels through plumbing.

Lead was commonly used in plumbing materials as recently as 2014, and this can be a problem for public water fountains, especially when they’re used by vulnerable populations, such as young school students. “Schools don’t really have a good way to address this right now,” said Louisville Water Scientist Mark Campbell.

Campbell noted that new fountains could cost $2,000 each, and they wouldn’t even solve the problem if other plumbing material in a building is made of lead. You could put filters inside fountains, but they’re difficult to install and replace.

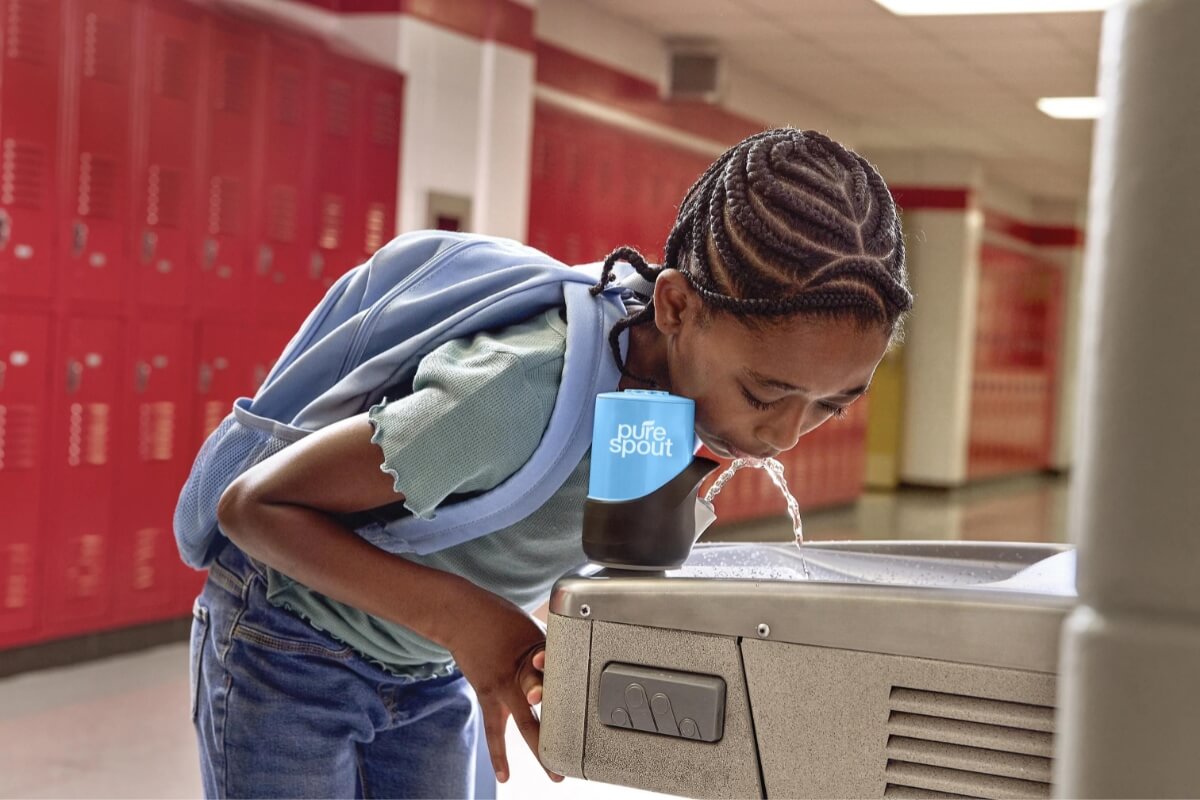

In early 2017, Campbell and Dr. Rengao Song, Director of Water Quality and Research — with help from Vince Monks, Distribution Water Quality Manager — came up with the idea for pure spout™, a filter that attaches to the outside of a fountain, directly replacing the old spout.

Pure spout will retrofit existing fountains and will use a replaceable filter cartridge with a proprietary design to remove contaminants.

Pure spout is designed to be cost-effective, sturdy, tamper-resistant, and easy to install. Customers also will be able to use a subscription service to keep filters fresh.

Matthew Griffith, Louisville Water Strategic Planning and Performance Specialist, has brought business expertise to the pure spout project and is helping bring it to market.

Griffith says pure spout aligns with Louisville Water’s focus on exploring new revenue streams. The company is considering several ways to expand revenue, including market expansion (such as regionalization, including wholesaling water to other counties), economic development (such as recruiting companies that use water to Louisville), and diversification (including new partnerships, services, and products like pure spout).

With any revenue-expanding idea, however, the company must answer several questions:

- How aligned is the initiative to corporate goals and objectives?

- Is Louisville Water well-positioned to sell the product in the marketplace?

- Is the project scalable?

- Does the project have adequate return potential, and can it reach profitability relatively quickly?

- Is the company ready to commit financial resources to support the project?

According to all of these measures, pure spout looks like a promising product, Griffith said.

Louisville Water is currently prototyping and testing the product and will be establishing other business functions such as manufacturing, sales, and order fulfillment. Soon, Louisville Water will launch a pilot program that puts pure spout in several Louisville schools for testing.

“This will give us a use case that will help us sell pure spout to a broader market,” Campbell said.

For more information about the product, visit purespoutfilter.com.